Back to the 80s: with food inflation nearing its highest level in 40 years, is the worst yet to come?

With food inflation approaching its highest level in 40 years, the cost of living crisis is the food industry’s biggest focus for the second half of 2022. Long-term targets such as net zero are relegated to bit parts when basic foods become rapidly unaffordable for many people. With Government leadership flailing around like a headless chicken and a feeble food strategy on the table, how did we get here and what on earth is going to happen next?

In 2019, Ukraine and Russia were peaceful players in global agricultural exports, COVID was an alien word – more likely the name of an IKEA dressing table than a cornerstone of our lexicon – while Trumpist nationalism and a Brexit vote were the height of our political tumult. Boris Jonson barely had his feet under the table at No. 10. Since then it’s been the stormiest period for our food supply since World War II.

The list of disruptions is long. I’ve cherry-picked some key points, luckily without the need for a seasonal worker visa to do so:

• Demand-side disruption during COVID, hammering supply chains

• Large-scale hospitality closures under lockdown

• Brexit border delays and import/export procedural turmoil

• Enduring seasonal workers shortages

• Lorry driver shortages

• Chaotic shipping price changes

• Energy, wheat and oil supply interruptions due to the Russian/Ukraine conflict

The magnitude of events has been so great that headlines paid scant attention to major food news, including Indonesia’s temporary palm oil export ban and the largest and longest outbreak of bird flu ever seen in the UK and Europe, which shut down the free-ranging ability of millions of birds.

The Office of National Statistics Retail Price Index has reported that food inflation hit 9.4% in June 2022, the highest level we’ve seen since the 2008 financial crisis. If it breaches 10.3% it’ll be level with the sky high inflation of the 1980s. The United States reported food inflation of 10.4% in June and most countries are seeing food inflation figures exceed overall inflation.

Professor Tim Benton of Chatham House is keen to make clear that it’s not food shortages driving up costs. “This is not an availability problem, this is a price problem,” he states. Healthy food and environmental concerns become more challenging in these conditions. “Economically marginalised people in every country in the world typically spend a larger proportion of disposable income on food,” he says, “increasingly they are forced to trade down in quality, reduce purchases and skip meals.” Hopefully poor Boris won’t need to visit a food bank once he’s collected his P45, but if so, them’s the breaks, eh?

The food system is like the South American cocaine trade. If one part of the supply chain gets knocked out, new supply lines quickly appear, filling the gaps, occasionally substituting with a different product or a lower grade, and sometimes bumping up the price. An average supermarket contains 30,000 SKUs and it’s rare to see more than a handful empty, which is a tremendous feat given the scale of disruption.

The Russia/Ukraine impact

It’s hard to overstate the combined significance of Russia and Ukraine’s contribution to food. Together, the two countries contributed 25% of the global wheat trade, with Ukraine alone responsible for up to 46% of global sunflower oil production. The invasion of Ukraine drove up the price of key agricultural inputs – energy and fertiliser – due to Russia being the largest fertiliser exporter in the world whilst also supplying 40% of EU natural gas and 27% of its oil.

Ukrainian fields are strewn with dormant mines and transport within the country is severely limited, which means the harvest this year is expected to be at least 30% lower than usual. Russia has strategically targeted port cities in Ukraine, creating an additional barrier for Ukrainian food exports, while Russia is allegedly aiming to use the ports to export their own goods. Despite the conflict, the demand for Russia’s exports remains high.

Poland and other countries near Ukraine are also seeing food inflation reach levels up to 20%, which Polish prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki has dubbed “Putinflation”. The effects of conflict cause fast-spreading “risk cascades”, as Tim Benton calls them, where negative impacts wreak havoc in countries far removed from the event, and the UK is far from immune.

Social unrest

Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit and vegetable trader, self-immolated in December 2010 as a protest against police treatment amidst high food prices, sparking the Arab Spring. While Britain is a long way from a revolution, protests have begun to appear in typically British fashion. This month, a part-used tub of Lurpak butter was listed on eBay for £400, a subversive display of derision at high food prices.

Severe food price increases typically coincide with significant periods of political unrest, as seen in 2008 and 2011.

At least 12 countries have already seen protests relating to food prices this year. Cypriot dairy farmers staged fierce protests, dumping milk and lighting hay fires outside the presidential palace, when production costs surged 115% without a concurrent increase in pay. Sri Lankan president Gotabaya Rajapaksa was forced to flee his country following demonstrations about the economic crisis, including food shortages.

Brexit also put a spoke in the wheel of British horticulture, as seasonal workers abandoned UK farms, and for good reason, leaving farmers with a fraction of labour needed for a full harvest. Travelling European labourers can work across the EU without a visa, for similar levels of pay. Working in the UK requires a visa, meaning we have little to offer aside from increased bureaucracy, unpredictable summer weather and the joys of a P&O ferry crossing.

The London School of Economics squarely pins a 6% increase in food prices on Brexit, caused by increased documentation and delays at the border, leading UK food businesses to hold more stock. The spice market immediately re-routed to avoid the EU. As soon as the new EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement came into effect, EU food imports significantly dropped.

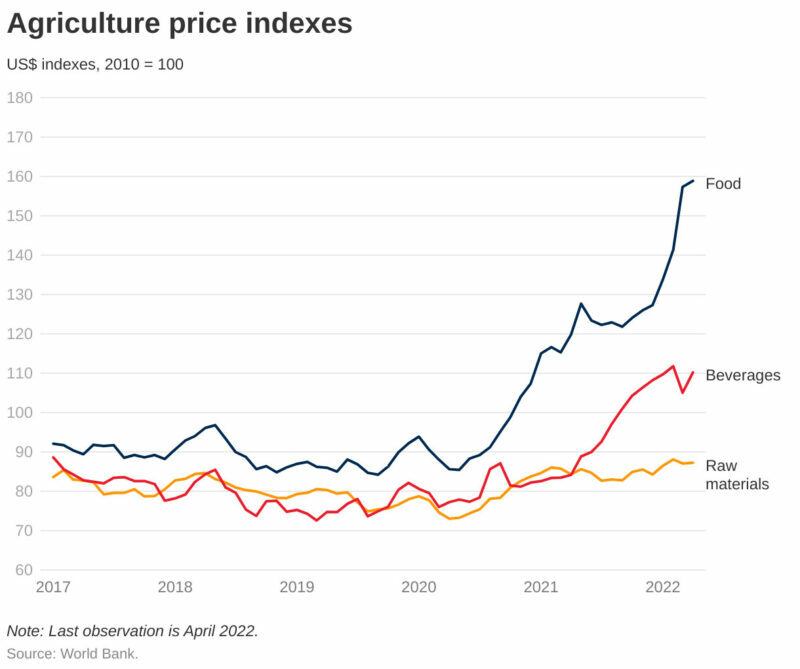

The World Bank food price index is up 33% YOY, with maize and wheat prices 44% and 15% higher. European wheat prices have jumped 52% and benchmark palm oil futures went up 25% since January. Fertiliser prices have doubled and natural gas prices have tripled in the last three years.

Agriculture price index.

Agriculture price index.

Bare facts from many sources expect inflation to reach at least 20% in the UK before the end of the year. Interest rates have hit a 13-year high and are expected to rise further too.

France has set limits on fuel price increases and has proposed food vouchers for those on low incomes to allow them to buy more healthy food. In the UK, Government action on food is flimsy. HFSS regulations were watered down on the pretence of assisting the cost of living, an audacious statement unsupported by evidence. There is nothing to insulate vulnerable people against price rises, and while the Government’s leadership is shakier than the criminal investigation into Ghislaine Maxwell’s client list, we’re unlikely to see much on that front either.

The Department of Health and Social Care is due to release a health disparities white paper in the autumn, a rapidly moving target this year, which could provide some assistance for policy. Tim Benton is circumspect. “Come the autumn we could face a very real crisis across the rich world as people are forced to choose between eating and heating.”

Farmers will be shouting louder about proper pay. Egg producers are only receiving an extra 4p per dozen free-range eggs, amidst 20p increases in shops, leading to flock reductions or worse, the possibility of cutting corners. If inputs such as fuel and fertiliser continue to rise then it will have a significant impact on farmer choices. The twofold price surge in oilseeds caused by the Ukraine conflict has already led some UK farmers to increase the amount of oilseeds they are planting.

Price rises, especially for consumers, will continue for the remainder of 2022, with agricultural prices expected to begin falling in 2023, as some of the recent disruptions unwind. With the energy price cap tabled to rise again in October, it’s going to be a while before we return to the buoyancy of pre-COVID days.